Chapter 4

Belgium

From 1st June 1915, until 9th August 1915

1.6.1915

It was indeed difficult to keep awake during my tour of duty from midnight until 2.00 am on Tuesday 1st June 1915 and I was very thankful when it was time for me to sleep.

I was again on duty from 8.00 am until 10.00 am, during which time I partook of a biscuit and some "bully". After this I once more "turned in" until duty again called, and then we all had a meal (4.00 pm) which, however, resembled very closely the previous one, as no fires were allowed to be lit on account of the smoke caused, which would inform the Bosches that these trenches were occupied, and so call fourth a shower of shells.

There are a great number of lines of trenches in this district, many of which are not occupied, and it is interesting to watch the Germs shelling empty trenches - they no doubt thinking that the casualties inflicted been very heavy - and putting it in their "official communiqué".

All day the bombardment on every side was absolutely awful and we all had severe headaches but of course had to "stick it".

2.6.1915

On Wednesday 2nd June we watched the Germs have another "go" at the tower of the Cathedral, and they struck it several times scattering chunks of masonry in all directions.

In at the evening we've moved along about half a mile to our right; the right flank of the Battalion holding the railway line by Menin road.

Until at this time our regiment had had the longer-Pattern rifle and a short bayonet, whilst the rest of the brigade had the short rifle and long sword.

The short rifle weighs about one pound less than the long, and it is more convenient and easier to manipulate, so that as the men get killed or wounded in the other battalions of our brigade, we had their rifles and swords. There was also a large number of arms and equipment of men who had been killed in a recent attack lying in front of our line in the open, and at night we would steal out and hunt for them, and share out.

3.6.1915

I got my fresh rifle and sword on Thursday 1st June and it was very clean and had an excellent barrel.

4.6.1915

On Friday 4th June the Germs shelled us on three different occasions; the first two times doing very little damage, but during the third shelling one percussion shell fell right in the trench amongst the men of my Company, and this one shell killed nine of my chums, wounded seven others, and three sustained shell-shock.

I would be here like to mention the names of three killed, who were particularly my "pals", they were:-

Corporal Matthews

Rifleman Kerl, and

Rifleman Mac. Gillervray

R. I. P.

The stretcher bearers went immediately to their aid, and one of them whilst carrying out his duties was himself severely wounded by another shell.

The shell which killed so many of these fine fellows went through the parapet and the men were buried under the debris. They were dug out, but were found to be beyond recognition, and the names of the killed were discovered by calling their role. This terrible result was the work of one single shell. Several other shells, to the extent of about 50, were fired at us, causing a number of casualties, more or less severe.

During the night a burial party made a large hole just behind the trenches in the which to bury their remains, and whilst on this unpleasant task came across a number of other bodies, and as the morning light was about to appear, our men had to be buried in the same spot.

5.6.1915

We were again shelled very heavily on a Saturday 5th June and the West Yorks had a large number of casualties. Our ration party was caught by a machine gun, and several men received leg wounds which provided for them any "ticket to Blighty".

I doubt if there was a day passed without a number of casualties whilst the Battalion was in the trenches in the Salient so I will not refer to the casualties except on special occasions, otherwise this will prove too sad and monotonous reading.

In the evening "A" and "B" companies moved up in to the fire trench.

On account of gas; the danger of working in the daylight; and other reasons work on the trenches was always done during the night, and no man slept between the hours of sunset and Sunrise, but during the day.

6.6.1915

We had just "turned in" at 6.00 am on Sunday 6th June, when the Germs commenced a heavy bombardment on our trench, which continued until about 9.00 am, so we lost three hours sleep on this day.

We were, however getting it used to this continued shelling, and were now able to sleep through quite a heavy cannonade, so long as the shells did not come too near.

The weather was a very hot, and we had one of our men down with Sun stroke.

7.6.1915

Nothing very special took place on Monday 7th June but as usual we had a number of casualties, and there was plenty of ‘tillery "knocking about".

8.6.1915

After a very sultry and "noisy" day (guns and thunder), on Tuesday 8th June, we were relieved from the trenches at 11.00 pm, and as we were going out the Germs treated us to a "dose" of shrapnel, and Lance-Corporal Newcombe of the signal section was wounded for a second time.

If anyone wants to have a little excitement I would suggest in the dark running up the field from Potiejze wood on a hot night, with full pack, rifle, equipment and 250 rounds of ammunition, and at the same time "dodge" shells by means of "belly-flopping". (throwing no one's self down in the roadway or ditch).

9.6.1915

We marched through Ypres without any further excitement as the Bosches were not shelling the town, and got on our way to some huts between Ypres and Vlamertinghe where we were to say, and at which we arrived at 2.30 am on Wednesday 9th June.

We were served out with some hot tea, after which we "turned in" and "turned out" again at 9.00 am.

There was a great shortage of water in this district and we were not allowed to wash with fresh water, so as to save it. There was however a stagnant pool a short distance away, so we made our ablutions there, although this was also forbidden on account of its filthy state.

Whilst coming out of the trenches last night, one of the signallers "belly-flopped", and lost his Telegraphic instrument, and as an excuse to look round Ypres in the daylight, I offered to go with him, and try to find it. (One man is not allowed by himself in case he is hit, and wants aid.)

We therefore obtained the necessary permission, with directions that we were to cycle through the town as quickly as possible, and we started off on our bicycles at about 2.30 pm.

Having got somewhat used to the conditions of affairs in Ypres, we were not so staggered by the sites, but rather looked on them in the light of sightseers-especially as it was daylight.

I must admit that we got off our "bikes" and walked slowly through, and by this means that a good opportunity of looking thoroughly at the town. On the sides of the road the bones and skeletons of dead animals, which had been burnt (as the best and healthiest means of their disposal), were stacked high in small piles, many of which were still burning.

We walked round the cathedral and Cloth Hall, but as the day was hot and the smell correspondingly strong, to say nothing of a few shells coming unpleasantly near, we did not stay long in this vicinity, but made our way to the Easter portion of the town by the moat. As however, the cemetery was nearby it was not too nice to be at this spot either. We had a look at the graves, many of which had gaping holes in them, and the tomb stones smashed to atoms.

Without having found the instrument, we "about turned" and again went through Ypres, and got on the road to Vlamertinghe (about two miles behind) and made a few purchases, returning to our "rest" camp at six o'clock. I created somewhat of a record at letter-writing during the evening. I went on duty at 10.30 pm and wrote letters without a break until four o'clock on Thursday, the 10th June, when I came off duty and slept until 8 am.

10.6.1915

It being considered that we had had a good "rest" (nearly two days) we moved up to a line of trenches on the banks of the Yser canal.

The actual trenches were about 20 yards from the river, but as they were about a mile from the front line, we did not stay in them, but in "dug-outs" built in the banks, which sloped steeply towards the river.

This position was considered very nice as there was a toe-path along which one could walk, and bathing was also permitted, and the Germs did not shell this spot more than two or three times daily.

(After a time, however, bathing had to be stopped on account of the Bosches dropping their dead into the river which flowed in our direction. Later on a German shell broke the lock-gates, and the water ran out, leaving only a small depth, the greater part of which was mud).

As there were not enough "buggy-hutches" to go round, the signallers set to work to build one.

We dug out a deep square in the banks, about 9 ft by 6 ft, and completed this operation by 9.00 pm. It was too dark to finish this evening, so we arranged some poles across the top, and put our waterproof above, and were just about to settle down for the night when it began to rain, and it ended in a deluge continuing through the night.

Of course the rain and broke down a our temporary roof, and we got the full benefit of the water, but never daunted, we laid down and covered ourselves with some sacking.

Although I had had only four hours rest the previous evening, I could not get to sleep as the rain made so much noise, and kept beating against my face. The others being in the same predicament, we decided to stand up for a time, until at the rain stopped, in a corner which had a space where the rain could not gain admission.

We chatted for about four hours, and were all thoroughly soaked, when we heard a call for "stretcher bearers".

We went out, and discovered that the rain had caused a "dug-out" to collapse, and bury four men. We therefore set to work to remove the earth and take them out, and managed to save three, the fourth however being beyond aid by the time we got at him.

This, none too pleasant occupation, made us nice and warm, and with the aid of the wood from the broken "buggy" we made a good roof for ours which kept the rain out, and after a cup of tea (made with fairly warm water, boiled on candle ends) we "turned in" at 5.30 am for the night.

12.6.1915

As dusk was falling on Saturday, 12th June, a Zeppelin flew over our trenches at a quite low altitude. The night was very dark, and the "Zepp" was spotted quite accidentally by a man walking along the trench.

We immediately reported the event (I was on duty), and were afterwards informed that the message reached London in 12 minutes.

During the afternoon the Germs shelled heavily the village of Vlamertinghe.

13.6.1915

On Sunday morning I was rather anxious to get to Church if possible, and as a cyclist was wanted to go with a dispatch to the Transport Lines (between Vlamertinghe and Poperinghe) I made arrangements, and got permission to go to Mass in the Church at Vlamertinghe.

I started off at 8.00 am and skirted Ypres, and arrived at Vlamertinghe in about half an hour.

The Church was the object of the Germs shelling the previous day, and it had been set on fire by incendiary shells, and now only the walls were standing, and it was still burning.

It had indeed been a stately Church, and the tall tower, although it had been hit, was still standing. The Germs desire, no doubt, was to smash the Tower, but in this they were frustrated, as was a I from attending Mass.

Apart from the Church, the village itself had not been severely damaged, and people were still living nearby. (I have lately met men from this district, and am told that Vlamertinghe is now a mass of ruins, and Poperinghe in is almost as bad).

I got to the transport, and returned to the trenches after delivering my message and had a swim in the river.

14.6.1915

During the evening of Monday 14th June, we went into the environs of Ypres "finding" tables, chairs, and other furniture for our "dug out".

15.6.1915

On Tuesday 15th June we were told to be in readiness for an attack which we were to make up on a line of the German trenches near Hooge, and as this was our first attack we were rather excited, and we had a swim to cool down.

We were to be in the second line, and half of the Battalion were to move into the trench as soon as the line was taken.

The battalion moved up at 8.30 pm, but as I was detailed to wait until relieved by a Brigade signaller, I went forward at 10.30 pm with the Colonel and Adjutant.

It was a terribly dark night, and we made a away over a number of fields containing many shell holes, and we occasionally came to earth. The Germs star shells however, helped us considerably to see our way, and after traversing about three miles of fields we arrived on the left of the village of Hooge at midnight.

With another signaller, I had to open a new station about a hundred yards away from headquarters in case the battalion got cut off, so that as soon as I arrived I had to lay a wire and get connected up. This work was completed in about half an hour, and it consisted of a great deal of travelling on the stomach as the Germs were firing rather heavily, and the line was made above the trenches. After completing we managed each to get an hour's sleep before operations commenced.

16.6.1915

At 2.30 am on Wednesday 16th June, our artillery sent out "feelers", and at 2.45 am, the bombardment commenced in deadly earnest. The daylight had hardly appeared, but the bursting of the shells lit up very vividly the lines of trenches. The Germs replied at once by shelling our trenches with high explosives of a heavy calibre, and the noise of the guns and the bursting shells, was terrific.

Within an hour, three times our telephone line was broken, and I had to go out over the top to mend it. Unfortunately there was a farm in front of the line and the Germs shelled it heavily in case ammunition was stored there. Our wires ran at the side of the farm, and consequently ware so often broken.

After a bombardment of an hour and a half, the front line charged and, as we were told later, altogether four lines of trenches were taken on a front of about a thousand yards.

For 4 hours this ceaseless bombardment continued, and at 6.40 am we received the following message:-

"All goes well aaa We have captured the enemies first line".

Just before receiving this message we were wondering how things were progressing in front, and were rather worried about having no news, when we saw a batch of German prisoners under our guard coming along the Menin road. This informed us that we had at least been successful in breaking through.

For some reason or other the Germs fired on their prisoners coming along the road and the prisoners and our guard had to scatter and lie down for a time, but none tried to escape, but hurried to a place of safety where they paraded together and marched off under the guard.

It is possible that the Germs fired on their own men on the principle that "dead men tell no tales", but whether this is the case or not, they did it intentionally for they could distinguish the Germs from the British and could have held their fire from the spot where they were.

The bombardment continued fiercely until about 1.00 pm and on our men reaching the second line, the Germs counter attacked with great severity, but were repulsed, and our casualties mounted high.

We received the following message about midday:-

"Each Third Division reports situation rather obscure aaa After reaching the enemies of second line of trenches on a line running up from a point J.13 A 4.5 in a S. S. E. direction through BELLEWAAR FARM to about J 12 D 1.2 the Germs shelled them very heavily and our line had to retire in places aaa The Germs commenced a counter attack against centre of line aaa this counter-attack appears to have been driven back by the observation of the F. O. O. (Forward Observation Officer) who could see enemy retiring and losing heavily from our rifle and gunfire aaa about a hundred prisoners belonging to the 27 reserve division and 15th Corps have been taken."

The approximate times of taking the trenches were:-

First line - 4.15 am

Second line - 6.00 am

Third line - 8.15 am

Fourth line - later in the morning.

Only a small party penetrated the fourth line, and they had to retire as the Germs counter attacked before more men could be got up. For safety's sake our men also retired from the third line as the trenches were so badly smashed that they afforded practically no protection.

During the afternoon the Germs sent over a few gas shells, but the winds being rather strong it was very little use to them, and we did not even put on our respirators.

The afternoon was somewhat quieter, but the battle commenced again at six o'clock when the Germs subjected us to a very severe bombardment for an hour, which they followed up with a strong attack, and our men had to retire. We now held only one line.

For some purpose-the reason of which I cannot say-during this counter-attack our guns were practically silent.

The Germs were bombarding us terribly, and our men were falling over like ninepins, but not one of our guns as far as we could tell, belched forth their death dealing missiles until the Germs were about to attack, when they opened up with shrapnel practically making a curtain of fire. This procedure may be the best if the signalling wires are not broken and the S. O. S. message (the call sent when the enemy is seen to leave the trench to attack) can be got through to the Batteries Artillery, but if the lines are broken, which invariably is the case, it has to be left to the infantry to repel the attack after they have been subjected to a severe bombardment.

I do not think that at this time it was a case of shortage of shells for we saw tremendous stocks of ammunition in certain places before the attack, and some artillerymen to whom we were speaking said that it had been brought up for attack, and that we had more handy.

The same procedure was carried out at Hooge on the 9th August (about which more later) when the papers said that it was the first engagement when we could say that we had enough shells, and it seems to me that it has rather a demoralising effect, and I shell certainly say that all our men would have felt happier if only a few of our guns had been firing on the German trenches.

As evening fell the firing became a more normal and the night passed without any further attack, we holding one line on a ridge on the left of the village of Hooge.

Twice during the night the Germs broke our wire, and I had to go out and mend it, but although it is more difficult to trace the break, it is not such a bad job as when it had to be mended in daylight under observation of the Bosches.

The importance of keeping up communications cannot be exaggerated, for if the line is broken messages have to be taken by hand, and apart from the length of time this method takes, it is very dangerous for the signaller who may not get through.

17.6.1915

The Germs did not counter attack on Thursday 17th June, the reason no doubt being that the night had given us an opportunity of consolidating our gain.

During the morning the Germs happened to "fire" one of our ammunition stores, and a great deal of noise resulted thereby, the heat making the bullets explode, but apart from the waste, no damage was done.

There being no signs of a another counter attack by mid-day, I decided to "turn in" (for we had been up all the night) when the Germs broke our wire, and again I had to mend it.

The regiments taking part in this attack besides our own were: -

Liverpool Scottish (the regiment which came over in the boat with us to France).

Royal Scots and Northumberland Fusiliers.

I understand that the Liverpool Scottish who made an attack he immediately on our right lost about 50% of their men.

The official report for such an engagement would be: - "Some ground was gained around the Ypres Salient on the 16th instant".

I was informed that about 50 Germs dropped their rifles and surrendered to the Royal Scots, but I cannot vouch for this statement, although there is no reason why it should not be true.

At 10.00 pm we were relieved and went to the line of trenches on the canal bank where we rested for the night.

18.6.1915

We did not rise until a late hour on a Friday 18th June, and after a swim in the river, we had a good breakfast (tea, ham and bread).

During the afternoon I went with an officer to arrange billets for the battalion in which to rest, in huts between Vlamertinghe and Poperinghe. The huts between Ypres and Vlamertinghe at which we had stayed previously had been shelled and were untenable.

At 10.30 pm I met the battalion on the main road and guided them in, and myself "turned in" about midnight.

19.6.1915

A walk through the woods in the morning, and a cycle ride into Poperinghe to obtain tinned pineapple (Crosse and Blackwell's) in the afternoon, was my programme for Saturday 19th June 1916.

It was about this time that it became possible and to obtain luxuries unheard of at the Front before, such as tinned fruit, condensed milk and other commodities (at a price) similar to those obtained at home, and they were indeed a godsend. As an indication of the price, however a fair sized tin of fruit cost 2.5 francs (about two shillings), and riches were indeed a blessing under these circumstances.

20.6.1915

On Sunday morning, 20th June, I attended Mass which was held in a field nearby, with a Signaller T. Buckley (since killed in action, RIP) and in the afternoon had a sleep in the woods.

I was on duty from 4.00 until 8.00 pm and an interesting message was sent showing our strength. The strength of an infantry battalion of is about 1,000, and our strength after the attack was: -

Riflemen 370

Signallers, machine Gunners, stretcher bearers etc. 120

Sergeants, Corporals, and transport 203

693

Which shows a deficit of 300 men.

21.6.1915

During the evening of Monday 21st June, an open air concert to which we invited the East Yorkshire Regiment, was held and much appreciated.

22.6.1915

I walked to Vlamertinghe for a "bath" at 6.30 am on Tuesday 22nd June 1915, and was on duty for the rest of the day as the Battalion cyclist.

23.6.1915 / 24.6.1915

Wednesday and Thursday were days of practically complete rest and preparation for another turn in the trenches.

25.6.1915

The weather had been a very good the past few days, and on Friday, 25th June, We were for the trenches again, and we decided that the dryness would permit of our going by a roadway called "High Street", made by the engineers through fields, and so avoided going along the main road which was subject to heavy shell fire.

When the weather was dry "high street" was quite good, and, as a matter of fact, easier to march on than the cobbled road running through Ypres.

At 1.30 pm we left the huts, taking a hand cart (obtained in Ypres) in which to put our signalling stores, and reckoned to do the distance of about eight miles to the trenches by 4.00 O'clock.

We had pushed a our cart for about two miles singing cheerily, when the "clerk of the weather" decided that the rain was wanted for the crops, and we got caught in a severe thunderstorm. Our ardour was severely damaged, and the Cart began to pick up a large portions of the Fields (to which it was not entitled) and expected us to push it along with its ill gotten gains adhering to its wheels. (It must have seen some of us in Ypres).

I cannot say the number of times it got stuck, but the language occasioned by this cart must really have made it feel ashamed to have been built. I will say, however, that when on a hot day one has a thick uniform, equipment, pack, rifle, and ammunition, and an uncomfortable waterproof sheet over one's shoulders, which persists in a placing the rain in one spot to soak through the clothes, it is no joke to push the cart laden with the heavy instruments, which does not agree to be pushed. Another point which makes things awkward is the number of a shell holes which have to be negotiated. Twice when the size of the shell hole did not permit of its being skirted, we rushed it down the hole, and up the other side, and, sad to relate, twice did the cart overturn, depositing its goods in the mud and losing various portions of itself.

We tried to hurry on as the Signallers in the trenches were waiting to be relieved, but after a time we had to abandon the idea of hurrying and took it gently. The rain lessened slightly, and we got to a cobbled road on the North of Ypres where we sat down for a rest, thinking we had finished with the "High Street".

The climax was reached when we were all lying down on the wet ground somewhat exhausted, when a Colonel came along and we did not get up and salute. The Colonel stopped and called the sergeant and demanded why we had not stood up and saluted!! The sergeant explained that "in the Field" it is not necessarily to salute, but the colonel said it was, and reprimanded the sergeant adding "I suppose you have just come out here, and think you can do as you like". On being informed that we had already been eight months overseas (which was probably much more than he) he seemed surprised, but said we were to remember another time. We were all standing by this time as we had been spoken to, and as he left we gave him a "salute", and I think it was well but he did not see it - nice man.

By this time the rain had increased, and we went a long distance out of our way to avoid "high street", and got to the canal bank by 6.30 pm. There being no chance of tea, we crossed the pontoon Bridge, and on inquiring our way to the particular trenches we wanted, we were informed, unfortunately, that we had to continue along "high street".

Two of the Signallers were so exhausted that we left them on the canal bank to rest in the rain, while we pushed on to the village of La Brique for which we were making. The rain was still coming down in torrents, and the last stage of the journey across small fields was indeed the "limit", and by this time, we were soaked to the skin.

We got to La Brique at 7. 00 O'clock, and by the side of a house, full of shell holes, an officer of the Leinster Regiment was standing, and upon seeing us covered in mud, smiled broadly, and asked us if we were having a nice time. On our assuring him to the contrary, he told us to "come in" (through a shell hole in the side) and he gave us all a cup of a hot tea and some biscuits; which proves that all officers are not typical of the Colonel referred to in a previous page.

We put our cart in the garden of a house nearby, which was being used as a dressing station (First Aid Post). The garden was really a cemetery for it contained a large number of graves of British soldiers who had been killed near the spot, and I may mention that before we came out of the trenches here, we had added quite a large number of the Queen's Westminsters to this burial ground.

The rain has ceased soon after we arrived here, and we waited until it was fairly dark so as to walk above ground and "risk it" rather than take the communication trench, which we knew would be full of water, and we arrived and relieved the Leinster Signallers at 9.30 pm; only about three hours late.

The trenches were full of water, but that did not matter for we were already as wet as we could be. The rain, however, did us a good "turn" for it had ruined the line to headquarters, and they had been running their messages by hand, and to open the station it would be necessary to lay a fresh wire. There was another Signaller with me, and we were both so "fed up" and miserable that we decided to say nothing about there being no line, and of course headquarters could not communicate with us and tell us to lay one, so we "turned in" after waiting up until midnight when the rest of the battalion came in, and we put them in their sectors according to Companies. There was a great shortage of "dug-outs" and many men had to sleep out in the open trench.

26.6. 1915

We were heavily shelled at 5.30 and 6.30 am on a Saturday 26th June but, except for four casualties, nothing out of the ordinary took place.

27.6.1915

It was decided to lay a our line during the evening, but as the supply of the wire was not forthcoming, we had to leave it for a time. He were quite willing, and "turned in" at 9.30 pm and did not wake until 7.00 am the next morning, when we were shouted at to get out of our "dug-out" as a shell had gone clean through the next but one to us.

We, however, felt as safe in our little "buggy" as out, and stayed there until the shelling had ceased, and then had another couple of hours sleep.

Sleeping during the night is forbidden around Ypres, but one gets into no trouble if not found out. Arrangements for work were made at night and sleep during the day.

It was decided that no station was necessary where we were, as there was another about a hundred yards along the trench, so we returned to headquarters, and I acted as cook for the Signallers there. During the night we built a "spanking" dug-out.

My duties as cook did not take up a great deal of time, the chief work connected with it being a walk out of the trenches every evening to the village of La Brique, for the rations.

28.6.1915 / 29.6.1915

I made my journeys for rations during the nights of Monday and Tuesday, and the Germs gave our "dumping" ground at La Brique a good number of shells, and also gave our trenches more than were required to allow us to have a comfortable time.

30.6.1915

As a punishment our artillery around Ypres received orders to shell heavily the Germs trenches, objects behind and also any of the enemies transport and "dumping" ground, on Wednesday 30th June, for one hour, commencing at 8.45 pm.

We were told officially that there it would be an "artillery display" at this time to celebrate the half year, so I'd got to La Brique early, and went into a house which had been shelled, and climbed to the roof, and with my friend, my pipe, - without which I could never have existed in the trenches - I watched through a shell hole as beautiful and terrible a sight imaginable.

The shell bursts kept lighting up the little village, throwing out the ruins in relief, and all round for miles one could see only a mass of fire.

The Germs did not reply. It seems as if they were "flabbergasted" by the magnitude of the display, and were waiting to see at which part of the line an attack was contemplated, if one was coming.

For an hour the sky was continually alight with bursting shells, making the blood red sunset more intense as it slowly past away.

Big shells, small shells, screeching above one's head, and bursting without a break with tremendous force. If for a second or two no shell burst, the noise seemed more intense as a contrast, and it sounded as if Hell had been let loose.

The roar of the guns ceased as suddenly as it had started, and the crack of rifles and machine guns could be heard, and this gradually died down, but for two hours I had to wait before it was safe to risk going down the road to the trenches. It would have meant certain death to have gone before.

No doubt the Germs were surprised at nothing happening, but we wait our time, and this was only an indication of what we could do. Six months of the year is completed, and we still wait, for we are not ready to strike, but the time is coming. .....

1.7.1915

It was to a very fine day on a Thursday 1st July, and I did my duty as cook.

We were very heavily shelled all day, and in the evening when I journeyed to La Brique things where very lively, and a continuous bombardment was kept up along the along road which I was going, so I decided that the pleasanter way would be across fields in the rear.

2.7.1915

On Friday 2nd July I carried out my usual duties as cook.

During the day the Germs fired some shells round our way, and one fell just behind our trench, but did not explode. As it was dangerous to men walking up to the Fire trench, it was decided to explode it when there were no men about; so, after smothering it with sand bags, a fuse was attached and it was fired.

It exploded satisfactorily and no damage was done. A minute or two afterwards a strong odour of flowers, such as one might smell in a death chamber, was evident, and we then discovered that it was an asphyxiating shell we had exploded, and we had "gassed" ourselves. A rush was therefore made for gas helmets, and although for a time it made our eyes "smart", no one was seriously affected.

3.7.1915

During the night of a Saturday 3rd July, We were relieved from the Fire trench, and went into the second line.

Our new quarters were about eight hundred yards from the Bosches and the line of trenches ran behind a thick hedge, completely obscuring the Germs view, but we could see through loopholes.

Behind the hedge a round tub had been placed, and from a ditch nearby I filled the tub, and proceeded to have a bath.

I got on very nicely, and was about to dry myself, when the Germs sent over a "Salve" of shrapnel, and I had to run for cover. Evidently they had noticed my "white" skin between some gaps in the hedge, and they objected to my ablutions without their authority.

During the afternoon the Germs bombarded us very severely and also sent over to us our first serious supply of gas and gas shells. We donned our respirators, and saw that our rifles were in trim with a nice Sharp bayonet attached thereto, and awaited developments. No attack came, however, and after a couple of hours we took off our respirators, but the gas hung about for many hours afterwards, and the smell gave all of us a sickly feeling.

The noise of a large gas shell going through the air is very peculiar, sounding like a tube train when one is waiting at an underground station, but when the shell arrives, unfortunately it does not stop at any particular spot, as does a train, but bursts where one does not want it to, with a loud bang, sending out clouds of smoke and gas.

A matter of about a hundred yards away from the line of trenches in which we were was the village of St Jean, which was practically ruined. The Church and cemetery around had been shelled, but the Church tower was still standing.

At 7.00 pm the Germs started a systematic shelling of this tower, and from my little "dug-out" I watched them trying to bring this tower to the ground.

Their shooting was really splendid; but even though they fired about 50 shells, they had to give it up, for the tower had very thick walls, and was most substantially built.

The cemetery attached was quite small, yet every shell fired either hit the Tower or Church, or else fell among the graves, and as the Bosches were firing from a distance of four to five miles (estimated by the time between hearing the report of the gun and the bursting of the shell) this performance was quite good.

Unfortunately the wind was blowing in the direction from the Church to our trenches, and the smell was really terrible, and actually necessitated our wearing gas helmets. Apart from this, however, it was a very interesting sight to watch from so near a point of vantage, and it gave us an opportunity of betting on whether the "next" shell would hit the Tower, or fall in our own trenches. (3 to 1 was the limit obtainable).

The Brigade Telegraph wires ran through this village of St Jean, and the shells had broken them. As soon as the shelling had ceased, a Brigade Signaller was ordered to carry out the necessary repairs, and as another man had to go with him for safety's sake, I volunteered for the job as I had not been into the village, and wanted to see the results of the shelling.

We crawled along by the side of the wires, keeping below the level of the hedge, (for we were well within the range of being seen, and bullets were plentiful), and eventually found the break, and mended it.

We then walked round the Church, and the first thing that came to one's notice, was a large crucifix on the outside wall, which he had escaped without damage.

The wall at one end was completely down, and that the other end were gaping holes where shells had passed through. Near the centre was the porch with the tower above, and on the wall, by the side, was a crucifix about 10 ft long, by some 6 ft wide, and the wall behind this crucifix was absolutely undamaged, although the wall on the other side of the Church, as well as the entire roof, was raised to the ground.

We then looked around the cemetery, and saw many graves opened by shell fire, bones, wood of coffins, tomb stones smashed, but noticed that several tombs stones made in the form of a crucifix, although the stone work comprising the cross had been damaged by shrapnel, the figure was still intact and unhit.

The Brigade Signaller with me as regards religion was "nothing" although designated for army purposes as "Church of England", but he also remarked on the wonderful preservation of the crucifix, and mentioned to me, that although he had not been to Church for many years, beyond attending Church parades, "there must be something in it", and we enjoyed, on our way back, quite an interesting religious talk, and it is very likely that good may result to both of us by what we saw this evening. One realised at this time how true is the expression "God's ways are not as our ways".

5.7.1915

The shelling was continuous on a Monday 5th July, and as my dug-out was not proof against shrapnel, I set to work to reconstruct it, and placed about three feet of earth on top as I did not want to finish my existence one night whilst asleep.

6.7.1915

Early in the morning of Tuesday 6 July, the British, at our left made a very determined attack, and succeeded in obtaining one line of the Germ trenches.

The Germs counter attacked at 10.30 am, and got their trenches back, and also attacked the line immediately in front of us. We "stood to" ready to go into the engagement at once. The Bosches in front of us, however, were repulsed, and we stayed where we were.

Through field glasses, I watched the enemy charge, which, although risky, was a sight I would not have missed on any account. It is seldom one gets such a position, as behind a hedge from which to watch an attack at close quarters, and without such protection it would be madness to try and see the charge. When an enemy is advancing, and one is in the Fire trench, one cannot take in the scene as one is about to fight for life, but being in the second line, with so much protection, gave me the opportunity.

With Major Cohen (our Senior Major) I watched the Bosches advancing and falling dead or wounded from our rifle and machine gun fire, and hardly a man reached our front line.

The length of the bombardment had not been sufficient to kill very many of our men, and there were plenty left to repel this attack.

At any minute we were prepared to counter charge should be Germs succeeded in penetrating our line, but we were not wanted, for the Fire trench was like a wall of steel, against which nothing could prevail.

Later in the day, the Regiments on our left again attacked, and took the line of trenches which constituted the original attack, and evening fell with us in possession.

7.7.1915

We "stood to" early in the morning of Wednesday 7th July, as the Germs counter attack very fiercely on the left, but they did not succeed in breaking the line.

In the evening I went to La Brique for rations as usual, and the firing was fairly heavy.

8.7.1915

Again the Germs attacked in front of us, morning and evening of Thursday 8th July but in each case they were easily repulsed. The firing was terrific especially at the evening attack, and first sight of the bursting shells which we watched through a gap in the hedge, was most appealing, even if rather uncomfortable when the shells came near.

Although I was "cook", and thereby relieved of all duties on the wire, I offered to do a couple of hours for another man, from 4.00 pm until 6.00 pm as he had had a heavy day on account of the attacks.

I "came off" at 6.00 pm and about 10 minutes later the Germs started shelling us with the "salvos" (four or six shells at a time) Which fell all around the Signallers office. The shelling there was so severe that we all had to "clear out" to the communication trenches (which is permitted in any trench but the front line if the shelling is very heavy, but of course, if attack is made on the Fire trench, we would all have to return to our posts) with the exception of two Signallers who must on no account leave while instruments can be worked.

As a matter of fact, all the wires were broken, and the Signallers left their office to report to the commanding officer that communication had been stopped.

They had no sooner got clear when a couple of shells landed - One in the Signallers office, and the other in an officers "dug-out" a couple of yards away. We kept clear for about half an hour, and then returned to our posts.

We then saw some very peculiar sights. A rifle in the signal Office had been twisted in a most peculiar manner, such as one might find a candle on a hot day. (It was suggested to use the rifle for shooting around corners). Everything was scattered about the office, and the roof had completely fallen in, covering everything with dirt.

The "dug-out" next door, had suffered in a similar manner. The officer, who occupied it, happened to have a shelf on which had been placed a pair of socks. On another shelf had been a drinking mug. We found the mug bent and battered, holding firmly in its mouth the pair of socks so tightly, that it would be impossible to pull them out without tearing them. This "souvenir" was sent to England.

9.7.1915

During the afternoon of Friday 9th July, I cut a short sap from my "buggy" (which was in front of the others some short distance) to a communication trench in the rear, along which to travel instead of walking over the top. Last evening I had had to "double" over open ground, in view of the Germs, when the shelling started, and I considered it was "not good enough".

10.7.1915

On Saturday 10th July, the Germs gave us plenty of "hate” and in the evening made another very determined attack on our left, and it was so serious that for safety's sake, the "trench log book", should be sent to Brigade Headquarters - about a mile back, on the canal bank.

I had just returned from La Brique with the ration cart, and was about to "turn in", when I was called up at 11.15 pm, to take the book to Brigade on foot, my bicycle having been smashed by a shell some time ago.

I had prepared for my night's sleep (which is not allowed) and my preparations consisted of taking off my respirator, and using it as a pillow.

As every man was wanted in the trench in case of casualties, I was ordered to go by myself, so I put on my coat, and saw that my rifle was in good working order and in the hurry and an urgency of the matter, forgot all about my respirator. (Gas mask)

In a blissful ignorance, I traversed the fields in the rear of the trenches, keeping behind a hedge as very heavy firing was in progress, and got to the road, when suddenly I sniffed - gas and I had no respirator! What was I to do? I dared not go back to the trenches as I would be going further into the gas area, and would very likely be overcome before reaching my "dug-out". I decided to hurry along; get to La Brique; and see if I could get a spare one there.

The further I advanced, the stronger the smell, which seemed strange to me, and not like the gas we had smelt before, but a more familiar smell, and at last I began to get the "wind up", and wondered what length of time I had to live, and why in the distance to La Brique seemed so long.

Suddenly I heard a gentle purr, and ahead I saw the outline of a cart. The smell grew stronger, but perhaps help in the direction of a respirator was near at hand.

At the same time, why was the smell getting so pronounced, especially as the wind was in front of me? Surely I was getting along quicker than the gas.

Suddenly the mystery was solved. It was not gas I could smell, but the fumes of about a dozen motor ambulances which had arrived ready to take the wounded to hospital, and they were all ready to move off, and emitting petrol fumes from the exhaust.

I cannot say that usually I enjoy the fumes of motor cars which often spoiled the sweet sense of the countryside in dear old England, but on this occasion nothing could have been sweeter.

I was so pleased with the smell that I gave a sincere sigh of relief and contentment, and then realised for the first time that the pathway across the fields along which I had to go was being shelled, and also the fields in the rear by the canal bank.

I tried to obtain a respirator, but no one had a spare, so I would not wait for the shelling to cease, in case gas was in reality sent over, which was more than likely. With another man on the same errand as I, from another Battalion, I started to cross. This other man did not know his way, and would not risk it by himself, but on my stating that I would not wait he "fell in" with me.

Every two or three minutes we had to throw ourselves to the ground as we heard a shell coming near, and suddenly a few yards in front of us there were four brilliant flashes and defining reports. We dared not move, for we were practically stunned. I then remembered that there was a battery of artillery in the Field, and discovered that we were walking straight towards the Guns!

It was a very black night, and the brilliant flashes had made it practically impossible to see at all. We crawled along shouting "battery, are you there?" - "friends here", or some such remark, when we were halted by a guard and taken to a "dug-out" where there was an Artillery Officer.

He told us to rest, and asked our business. On our informing him that we were taking the log to Brigade, he said we could not go on as they were shelling all round the brigade headquarters.

He asked us from where we had come, and when we told him "across the fields in front" he would hardly believe us, he said that it was impossible to live through such a bombardment as the fields had had. He told us that the Germs were trying to silence his guns, and that it was very dangerous here, (very cheerful) and all he did do, was to go out occasionally and fire his guns, and then return at once with all his men to the "dug-out".

We waited in the "dug-out", during which time he obtained for me a respirator (which put my mind at rest), and we then had a chat about my Regiment, in which he was interested as his grandfather, or somebody, had once belonged to it.

After about half an hour, the Germs transferred their attention to other directions, and we were allowed to proceed.

We found on arriving at brigade headquarters that the shelling was still going on, so we decided to get to the Signal Office quickly, which was nearby across the Bank of the canal, and get undercover there.

We got there and found the General and his staff sitting on biscuit tins, as their "dug-out" had been smashed, so we sat in there for about half an hour, and heard all the news as to the progress of the attack as it came through over the wire, finishing with a message to the effect that the "Germs just attacked and repulsed".

As things were now quieter, the General (General Congreve VC) told us we could get back to our units, and I eventually arrived in my little "buggy" about 3.00 am after reporting to the Commanding Officer, who asked me if I had to had a "good time", and saying that he honestly did not expect I would have got through.

11.7.1915

During the evening of Sunday 11th July, we were relieved by the Leicestershire Regiment, after a very trying period of 17 days in the trenches.

The Signallers were relieved a couple of hours before the rest of the Battalion, and we got to the huts between Vlamertinghe and Poperinghe, and "turned in", and were well asleep before the remainder of the Battalion arrived.

The return from the trenches is especially looked forward to by the Signallers, for the section becomes like a large family, and in the trenches we are separated and posted for duty, two or three at a certain station, where as the companies are of course always together. The nights on which we come out of the trenches are invariably very noisy amongst the Signallers, for we would all tell our various experiences at the same time, one to another. We consequently used to get into much trouble from the " 'eads" nearby, who perchance might desire to repose. However, in spite of the fact that we were always getting "jawed", they could not do without their Signallers, if only for the reason that there would be nobody else to cause trouble.

12.7.1915

On a Monday 12th July we had a general clean up, and inspection of kit etc. I did duty on the wire from 4.00 pm until 8.00 pm; my duties as cook having been terminated.

We got a draft from England of about 300 men, as we had lost so many lately, and the strength of the Battalion was again very low.

13.7.1915

We were up at 6.30 am on Tuesday 13th July, and paraded for physical drill.

Later in the morning we had "Buzzer" and Heliograph practice. Rather a funny incident was the result of the Helio work we did, and it was this way.

With a Helio it is possible to send messages many miles, as long as the Sun is bright, and we saw a long distance off what we took to be a Germ captive balloon.

We began to send messages to the balloon which were far from complimentary in character, and when we packed up we felt very pleased with our morning's work.

We had to keep very quiet, however, when during the afternoon a message was received by all units and local battalions to the effect that "during the morning a heliograph had been fixed on to one of our captive balloons, and objectionable messages sent by some person or persons unknown" and requesting that every effort to be made to trace those responsible.

With Rifleman Rhead, on completion of our morning's industry, I went to Poperinghe, and we had a good dinner at an estaminet, and made a number of purchases.

We returned in an empty motor lorry, and bumped all along the cobbled road from "Pop" to "Vlam", and we were by no means sorry when the journey came to an end.

14.7.1915

Physical drill again at 6.30 am on Wednesday 14th July, and afterwards duty as the Battalion cyclist during the morning, which necessitated two journeys to Brigade Headquarters in Poperinghe.

In the afternoon I again went to Poperinghe with Riflemen Rolfe, and had a bath.

Rolfe bought a luminous watch in Poperinghe, and as he wished to dispose of the one he had, I bought it for 10 francs.

I therefore had mine to sell, and on putting it up for auction I got a three francs for it, which, considering I bought it for rough usage, and originally paid 2/9d for it, was not so bad, especially as I had had it for nine months, and the glass was cracked. But then in France watches were very dear, and it really was a good time keeper.

15.7.1915

St Swithin's day Thursday 15th July was the occasion for more "physical jerks", and afterwards clothes washing (much needed).

I was on duty on the wire from 4.00 until 8.00 pm, and then attended a concert which had been got up by members of the Q. W. R.

16.7.1915

On Friday in the 16th July, we practised a system whereby we might be able to "tap" the Germs Telegraph wires. I might mention that we made sure that the system would not work, especially as it meant a Signaller going "over the top", as near the Germs lines as possible.

17.7.1915

We had a day off on a Saturday 17th July on account of heavy rainfall. In the evening we held another excellent concert in the open. The Q W R were not daunted by the rain which fell all the time.

18.7.1915

Sunday's morning 18th July, I attended at Mass in a field nearby, and in the afternoon was on duty from 4.00 pm until 8.00 pm.

19.7.1915

At 3.00 pm on a Monday 19th July, we left once more for the trenches, and at 6.30 reached Potiejze wood without too much excitement.

We had just arrived in the wood, when the British at Hooge (300 to 400 yards on our right) blew up a mine, which is now so famous, and where so many have since lost their lives, called the "crater at Hooge"; - and as this was the first big mine we had seen so clearly, we were astonished, and at first did not know what to make of it.

There was a tremendous report, the earth shook, and a voluminous mass of smoked floated upwards.

We then opened up with our artillery, and all the guns around were firing, causing a great deal of noise, and in the distance was a line of flame and smoke from the shells bursting over the Germs line.

A charge was then made, and the British succeeded in obtaining the positions which they were after.

Soon, the Germs recovered from the surprise of the attack, and began to bombard our line very severely, and the men in the British Fire trench suffered very large casualties.

There was a wireless station in the Wood, and after the Germs bombardment had been going on for some time, we had been watching it from positions behind walls, trees, etc; We were ordered to get into "dug-outs" at once, as a shelling of the wood was imminent.

The "dug-outs" were splendidly made, and had a thickness of some of five to six feet of earth on top, and were proof against shrapnel.

We had no sooner squeezed in when the Germs commenced a violent cannonade of shrapnel shells. We were then told that our wireless station had sent out a message in Germ, as follows: -

"British infantry amassing in Potiejze wood",

And this message had been picked up by the Germs, and they had taken their fire off the trenches and shelled the Wood. Except for the men in the "dug-outs", there was nobody in the wood, so no damage was done. The wireless station of course knew that only shrapnel would be fired, for slaughtering infantry on mass, and also firing into a wood, high explosive percussion shells would not be used.

We had about two hours of this bombardment, and then evidently the Germs discovered the trick and stopped shelling, and again fired on the trenches, but by this time it had given our men in the firing line a chance to recover. I expect the Germs were pleased with themselves for having been "taken in".

I had a chat with the priest attached to the Leinster Regiment who had just come from the trenches and he told me very many interesting anecdotes of a religious character connected with his regiment, and then, with another Signaller, I proceeded to relieve the Leinster Signallers.

20.7.1915

The companies did not arrive until half an hour after midnight on Tuesday 20th July. After putting up the company to which I was attached in their portion of the trench (which was on the left of the Menin road, and a few hundred yards from Hooge), I went on duty on the wire until 3.00 am.

The position of the trench which we occupied was as "lively" a spot as I encountered around the Salient, and we had an awful number of casualties.

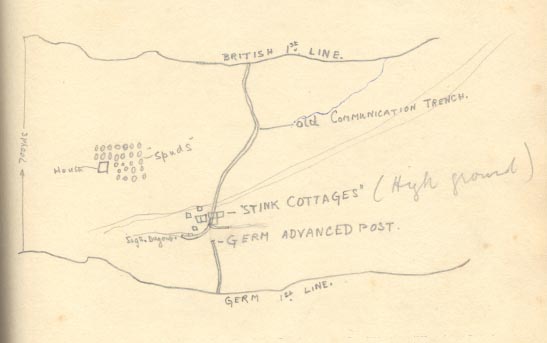

I will shortly be introducing "Stink Cottages", and to give an idea of this "health resort", I will mention the number of casualties daily out of 20 men who had to be there.

We were some 700 yards from the Germs, and about 50 or 60 yards in front of our line were two or three houses, with large gardens attached. Having heard that there was a good supply of new potatoes growing, I decided that the only way to obtain possession of them was to go "over the top" as evening was beginning to fall, take a sack, and dig them up. I made up my mind to do this, and about 8.00 pm I went over, and got about half way across, when an attack commenced at Hooge. I "carried on", however, and got to the houses.

I was gathering a large number of "spuds", when the Germs took it into their heads to commence shelling, some of which shells fell within 10 or 20 yards from me, between the trenches and myself. I decided that the spot was not too healthy, so I threw my sack across my back, and "doubled" across to the trenches, making a mental note to myself that I would go without potatoes in future, rather than fetch them in this manner.

The Germs made a bombing attack about this time at the "stink cottages", and we had one man killed, and several wounded.

21.7.1915

On Wednesday twenty-first July, are our Adjutant (Captain Flower), of the K R R C, left the Regiment on being promoted to the rank of Brigade Major, and in him we lost an officer who did excellent work in keeping the Battalion together.

As can be readily understood, the duty on the wire during the night was by no means the most congenial, and I was very the surprised when the Signaller at the station with me suggested that I should to duties on the wire during the day, and he would take all the night work. I readily fell in with the suggestion and discovered after about a week that his principal of doing night duty was quite peculiar to himself. I came off duty at 10.00 pm and he would do a couple of hours duty and put the instrument around his head and "turn in", and not wake up until about 8.00 o'clock next morning. Luckily for him he was not found out, but I could quite understand why he proposed night duty as in these conditions it was not very tedious or a great strain.

In the evening there was plenty of artillery round our way and another small attack at "stink cottages.” Consequent to this attack we had about eight casualties.

22.7.1915

At 7.00 am on Thursday 22nd July, the Germs attacked and bombed "stink cottages", but, this occasion our men evacuated the position and took cover at a spot about 20 yards behind, and when the bombing was over again advanced to the sap by "stink cottages" and gave the Germs a supply of bombs with interest. By this means we managed to avoid casualties.

There was much rain during the day and the trenches were practically water-logged.

In the evening I went across to the "White Chateau" in Potiejze wood and drew up a few extra rations. There was a great deal of shelling going on which re- echoed right through the Potiejze wood causing a tremendous amount of noise.

The casualties at "stink cottages" this day amounted to one killed and four or five wounded.

23.7.1915

Friday 23rd July was quite like a day in April being at times very fine and at others very showery.

The casualties on this day at "stink cottages" were four men killed, which included the champion boxer of the London Banks.

24.7.1915

At 6.00 am on a Saturday 24th July, the Germs without any consideration and of our feelings heavily shelled our trench and disturbed my peaceful slumbers. One shell which fell about 20 yards from me wounded five men.

"Stink cottages" again came in for a bombardment this time with trench mortars and aerial torpedoes, but no damage was done on a this occasion.

There was a fair sized farm just behind the Germs line which we designated "Krupp's Farm". In at the evening one of our star shells fell on some inflammable material in the farm and set fire to the premises. The light from the fire, which necessarily had to run its course, was very brilliant and lit up the whole countryside.

We were by that means able very often to spot the enemy bringing up his rations, working parties, etc and there is no doubt many of them carried rations for the last time.

Apart from this, it was a very fine sight seeing the farm one mass of flame.

Casualties at "stink cottages" this day where one killed and three wounded.

25.7.1915

Sunday 25th July was indeed an ideal day and like many other Sundays the firing was not very intense.

In it the evening I witnessed a sight which was as splendid a display of aircraft strategy I have seen. It came about as follows: - It is usual as evening is drawing to a close for patrolling aeroplanes of both the British and Germs to go up high behind their own lines to observe the movement of troops and transport that necessarily take place when dusk is falling.

It is very seldom that these machines, which are of a heavy type, go beyond their own lines or attempt battle.

Suddenly one of our machines left its course and went straight towards the Germs Lines. Three Germs machines came forward ready to offer resistance. Our aeroplane still went forward and the Germs closed in to attack. Our machine quickly turned tail and retreated, but we below were watching and could not understand the idea at all, when out of the clouds we saw a monoplane above the Germs machines which our aeroplane had drawn on. The monoplane dropped a bomb which caught one of the Taubes. The two Germs machines turned tail and retreated and the other burst into a mass of flame and began falling to the ground.

At the same time there rang out from the British trenches a tremendous cheer and the Germans opened up a rapid fire. Unfortunately one of our men got rather too excited and had his head above the parapet and was instantly killed.

The Observer inside the blazing Germs machine tumbled out and fell between the lines. The pilot made a splendid attempt to land, and we did not fire at him, as he was going in our direction so gave him a chance. He was, however, not content and made an effort to turn his machine round to make for his own line and we opened fire at him, but it is doubtful if he was touched. It was all ended in the space of a few seconds when the machine turned turtle and dived to the earth, falling behind our trenches. Both machine and pilot were burnt to cinders.

About 10 minutes after, a Germ aeroplane appeared flying very low right behind our trenches in order to spot where the machine had fallen with the object of destroying any documents or papers of value which might be in the machine. Our artillery did not fire a shot at this aeroplane, but after a few minutes the Germs commenced a heavy shelling round the spot where the aeroplane had fallen.

It was now my turn for duty at "STINK COTTAGES".

The name of "STINK COTTAGES" was indeed well earned for the position consisted of about five or six cottages which ran at the side of the communication trench from our lines to the Germs line. This communication trench was most important, for at one time the trenches in which the Germs were belonged to us, and they took them from us when the gas attack was made in April.

It was necessary to make sure that the Germs did not have possession of these cottages as it would have given them a position whereby they could fire into a our trenches on the heads of our men.

We therefore defended the communication trench right up to these cottages, when it was blocked up by refuse, dead bodies etc, for a space of 15 yards, the other side of the barrier being used by the Germs as their advance listening post.

25.7.1915

As will be seen from the sketch below, on account of the importance of the position the Germs kept making attacks, but we still retained the position.

The strain at this point was so severe that 24 hours was the greatest of length of time for any man to be there.

Every evening 20 men would be detailed to hold this sap for the night, and it was impossible to get along the sap during the day. Two Signallers went up every night with the 20 men. There was only one dug-out of a very disreputable character, which was used by the Signallers. When this dug-out was made, the digging party came across what was a woman buried in all her clothes. Evidently she had been killed when the cottages were shelled. There was a leg with a boot on which penetrated one wall of the dug-out, and it served as a table on which to work the instruments.

The height of the trench was no more than three feet, and one could never stand up nor do any work at all during the day or night to improve the position.

At about 8.30 pm, with my charm, I crawled along the four or five hundred yards to "stink cottages" and relieved the Signallers who had been on during the last 24 hours. One of them who was about my own age, had suffered so terribly from the strain, that his hair in parts, had turned quite white, and after his return from the trenches, he eventually got a to England.

We took over and telegraphed to through to headquarters that we had arrived.

The rest of the men were relieved one by one, and during this process, four men paid the penalty.

It was forbidden to strike matches but I managed by lighting by Pipe in the dug-out to set all the men smoking taking lights from one another's cigarette.

26.7.1915

All night long continual fire at point-blank range was carried out by the Germs, and the noise was absolutely defining, and of course we got no sleep.

We got a number of bombs over but no attack was made.

26.7.1915

During the day two men were killed and three wounded, and they had to stay in the trenches until night time before they could be removed.

Apart from the strain which these 24 hours had, I must say it was the worst time I have never experienced in my life. The atmosphere was terrible.

Just at the side of the sap was a dead horse, and the warmth of the weather had made the stench from the number of dead lying around most objectionable. I was indeed thankful when at about 8.00 pm we were relieved by two Signallers from the East Sherwood Foresters, and proceeded to the Chateau in Potiejze Wood where we met the first rest of the Signallers who were anxiously waiting our return.

We were detailed to go to the billets on the northern outskirts of the Ypres, and the Battalion were to do fatigues for other Regiments in the trenches.

Ypres, however, was being so badly shelled by "woolly bears" that we had to wait for some considerable time before we dare risk going through the town. Eventually however we went across some fields and got to our billets about midnight.

We were now about two miles from the trenches and were in houses, which, were more or less battered by shell fire. To make ourselves comfortable before turning in, we went to some houses nearby the "Water Tower" and obtained a supply of mattresses more or less clean. We marched proudly along the road with these mattresses on our backs and laid them down preparatory to "turning into". We "tossed up" for duty and I lost, so had to go on the wire until 4.00 am.

27.7.1915

On Tuesday 27th July, after duty I had what I considered a well earned sleep after a period of over 40 hours without sleep.

In the evening the Germs where thoughtful enough to send over a supply of gas which reached us in a large quantity, and necessitated us wearing our smoke helmets. The only "military" damaged they achieved however, was to deprive us of smoking for an hour or two.

After the "wind" fell I went for a short walk and came back when we had a "sing a song", to the annoyance of the sergeant major who presided next door. As sergeant majors never swear however, no doubt no harm resulted from this very enjoyable evening.

28.7.1915

I washed some clothes on Wednesday 28th July, and I really cannot say it wasn't necessary.

In the afternoon I was on duty from 12.00 until 4.00 pm, and the Germs again granted us another liberal supply of gas.

29.7.1915

I was on duty from 4.00 am until 8.00 am on a Thursday 29th July, and later on in the morning with two of my friends, "Dear and Chamberlain", decided to take the risk of a trip around Ypres.

I might say that these two were of a very adventurous and daring spirit, and did not mind at all whether we were caught, which, if had been the case when we were coming out of a house, we would have been liable to be shot.

However, we got through a number of orchards, picking a very good supply of nice fruit (there being no owner to object) and crossed over the canal getting into one of the main Street's of Ypres.

On our left we passed a big open space in which there were roundabouts, skittle alleys, such as may be seen at our English fairs, and everything as far as we could see was in working order, except for the fact that many of the parts were damaged by shells.

We made a very noble attempt to induce the roundabout to work but all our efforts in this direction were in vain. Even the barrel organ refused to give forth any melody.

However, we passed on our way and in the street where gaping holes where shells had penetrated right down into the sewage drains. On the other side were houses smashed beyond recognition, and a little further along the road we came up to the cathedral. There was no one in sight.

We went right against the cathedral and observed the bricks, masonry, glass and roofing piled high in an irregular heap of debris in the interior of the Church. The roof was completely destroyed and the sky could be seen overhead. Many portions of the walls were demolished, also the sanctuary except for the Crucifix which still stood behind the high altar looking down on the wreckage, and above the crucifix the roof was still intact.

We then a proceeded to the cloth Hall across the road and saw the paintings on the walls which were terribly damaged and smothered in dust.

We obtained various "souvenirs" such as pieces of masonry etc, but unfortunately I was not able to bring them back with me to England.

We had been in Ypres now for some of considerable time, and were forgetting that there was any risk of us being caught, when suddenly we heard the hoofs of horses going through Ypres. We looked about for a place to take cover and observed a number of niches from where the statues were removed, and we took the place of the Saints which had at one time occupied so prominent a position. Unfortunately we had all just lit our pipes and continued our smoke, which a Lynx eyed military policeman managed to spot and came round to investigate. On seeing us he remarked that we were as little like Saints as he could imagine and proceeded to take our names. There was also a French military policeman with him, and we had a long discussion apologising and trying to explain that we did not know we could not go in to Ypres, etc.etc. The yarn I pitched in my broken French punctuated with scraps of English was no doubt very impressive for we heard nothing more about the matter, and were very fortunate and got off without any trouble.

There was a five inch field gun in a field some 200 yards from our billets, and when it fired the percussion was so great that the house in which we all were shook violently.

In the evening with the same the two Signallers I went and had a look at the Gun when it was firing. The Germs began to reply so we hurriedly took to some dug-outs which were not far from the gun.

We were greatly struck by the simplicity in which these guns were fired (on the land yard principal) which seemed to us much more convenient than the way in which the ignition of a howitzer is made.

In the evening we had another supply of gas, and after it had blown over we went out hunting for nose caps. We found some, but they were so tainted with the smell of gas that we did not take them away with us.

We then "found" a chicken which was anxiously looking for a home, and after mercifully wringing its neck, sat in a shell hole nearby, and commenced the very trying occupation of plucking its feathers.

We also went into some fields nearby and "found" some peas and beans which we stuffed into a our pockets, and with light hearts and under cover of darkness we traced our steps towards home where we displayed our trophies making the rest of the section very envious.

We then turned in for the night.

30.7.1915

At 4.00 am on Friday 30th July, the Germs made a big attack at Hooge when they released the liquid fire, and thereby made the British retire from one line of trenches.

The shelling was a very intense, and at the same time they gave Ypres an unusually severe bombardment.

We were all ordered up and went out into the field some distance away, and the Signallers had no sooner got out of their billets when the house next door was caught by a shell and completely raised to the ground. After half an hour we again returned to the billets and turned in.

Later on in the morning we cooked our well won chicken, and it may be interesting as a recipe to enumerate the ingredients which we used in the process of stuffing.

We found in a cupboard in our house a quantity of flour which had probably been there since the owners evacuated many months previously. I then suggested in that the absence of the anything better, that an apple cut up into small portions would be very tasty this was agreed to by the company, a pear soon followed, two greengages were then cut up, peas and beans chopped up into fragments were then added. Somebody brought in a rat and other similar refuse, but that, under no consideration would we permit to be added to our already voluminous supply, and both rat and owner were unceremoniously kicked out without regard for either's feelings.

Considering the size of the bird, which, to us, looked as if it had been on "short rations" for many months, the quantity of stuffing which we managed to get in was indeed a very creditable.

The signal section who were not partaking in the chicken said that this was accomplished by the fact that each man would pull its neck, and by that means give more space to put in the stuffing.

We boiled the chicken and partook of it at mid-day with new potatoes, beans and peas, followed up by stewed greengages which was greatly enjoyed.

During the afternoon there was another attack at Hooge, and we were again shelled out of our billets, so, to get out of the way, we went to an estaminet not far from the Guns, where we were entertained very socially by three nice little girls who were still there are selling "milk" to the troops.

I was on duty from 8.00 pm until midnight.

31.7.1915

We got up at 8.00 o'clock after a night of heavy bombardment, but we did not leave our billets as the shells were not so near as they were the night before.

The shelling however, for the past day or so had been a very intense.

In the evening we were ordered to dig some trenches not far from our billets, to which we were immediately to proceed in the event of our billets being shelled.

At 9.00 O'clock in at the evening there was another attack at Hooge, and we were ordered to "stand to", ready to go into the battle, but by midnight we got orders that we were not required, and were therefore able to partake of a repose.

1.8.1915

On a Sunday 1st August, things were a bit quieter and we had a general clean-up.

During the afternoon the Germs shelled us very heavily with 6 inch shrapnel and gas shells, and as we had not completed our digging operations, we had to take to the cellars which were available.

2.8.1915

On Monday second August, we had a very liberal supply of shells at our billets.

We got orders during the afternoon that we were to leave Ypres and go to Poperinghe, and at 6.30 pm proceeded on our way past the water tower, Gaol and asylum, and got on the road to Vlamertinghe.

I might here mention the wonderful defences which were between Ypres and Vlamertinghe, the details of which, although interesting, I must refrain from stating for obvious reasons.

On of the road three or four of us stopped at an estaminet and partook of a certain amount of "joy water", and we got detached from the rest of the signal section. They however, had left us the truck in which were the Signallers instruments, and we had to push it all the way to Poperinghe.

It was a very dark night and rain was beginning to fall, and when we got to Poperinghe, in order to find the rest of the section we used signalling lamps sending our "Q W R" call, thereby getting into trouble with the military police who came over in a rush to see who was signalling.

Eventually we found the rest of the section and took up our billets in a convent in which there were a number of the Sisters of the order of "Petite Soeurs des Pauvres".

We eventually turned in about 10.30 pm.

3.8.1915

We got up about 9.00 o'clock on Tuesday the 3rd August, and the air was full off rumours.

The first rumour that came through was that we were going to leave the Ypres district, hence our going on to Poperinghe. Later it was rumoured that we had got a few days grace preparatory to going into a big attack, and this latter proved to be true.

Nothing very exciting happened today, and we finished up with a convivial evening at an estaminet where one was able to get bottles of very good champagne for the moderate sum of three and a half francs.

In this town we were able also to get the Belgian shag tobacco, eight sous a pound and first class cigars for two sous. The Belgian tobacco I, personally, rather liked once I'd got used to it, but the French tobacco I could not stick at any price. However, as we were issued with English tobacco as a ration, I did not often take advantage of the Belgian shag.

We turned in at 10.00 o'clock, and during the night the town was very heavily shelled.

4.8.1915

On Wednesday 4th August, with my chum Dear (whom I am sorry to say has a recently been reported "missing"), I went round and had a look at the damage which had been done, which, considering the ferocity of the bombardment, was not very excessive.

We went his inside one of the churches in Poperinghe which had been slightly damaged, and there was as beautiful an old carved pulpit as I have ever seen. It was a great height and all hand carved, and I was told that it was nearly 1,000 years old.

We had dinner out and finished up the day with another convivial evening.

5.8.1915

On a Thursday 5th August, we had orders to prepare for a journey to Ypres.